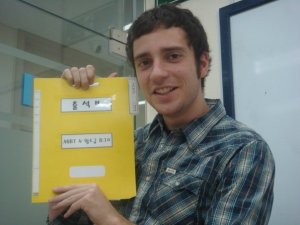

Can you ever imagine listening to a guy like this? The answer for most students seemed no.

The initial response I gathered upon announcing my intention to teach English in Korea provoked some playfully derisive skepticism from friends and family. Most of this stemmed from the fact that I have a very low, gruff voice that tends toward mumbling and often renders me incomprehensible to listeners. I’m also infamous for mispronouncing certain words, namely “archive” with a soft “ch” instead of a hard one.

However, I had my own personal doubt that I thought would far exceed my sometimes garbled speech. Teachers, especially those of young kids, need to possess a presence that commands authority. Ever since I tried (and failed) being a patrol leader in Boy Scouts, I’ve known that I lack leadership qualities as such. I can’t really summon the kind of demeanor or personality that would instill terror in the heart of anyone, especially misbehaving Korean children.

I said to hell with it and flew over there anyway. Plus, I expected that upon arriving I would undergo a week or two worth of training to compensate for my complete lack of teaching knowledge. Instead, I arrived for my first day of work, was handed a stack of books and a schedule, and then shoved in front of a classroom of 12 nine-year-old children with absolutely no instruction as to what I should do with them.

Deep breath.

The kids were enthusiastic enough, gleefully shouting out the names of objects as I pointed to them in the class book. “Bee!” “Flower!” “Lizard!” Okay, fun enough, but it took all of about five minutes to knock out the first two pages in the allotted six for the entire class. I looked up at the clock, at my increasingly talkative (not in English) students and realized with dread that I had another 45 minutes to kill.

It was a rough first day.

For the next six months, I struggled for control. I tried making jokes (went over their heads), yelling fiercely (they couldn’t understand what I was saying) and giving up (class time = game time!), all to no avail. Overall, my approach’s defining characteristic remained its inconsistency. Depending on my mood, the boundaries about what constituted acceptable behavior and not shifted. This made enforcing rules difficult on the rare occasion that I had the courage and energy to enact them.

All this frustration culminated about halfway into my year-long contract with a physical altercation. There are no laws in Korea forbidding corporeal punishment, and Korean teachers often carry thick bamboo sticks with them to class. I had on occasion tapped kids on the head with a marker or folder to get their attention but never with any force behind it. On this particular day, I found myself so annoyed with an individual kid that I lost my temper, rolled up a book and swung full force at the standing boy’s head. Lucky for him (and me, in retrospect), he nimbly ducked under my brutal swing, resulting in gales of laughter from his classmates and extreme embarrassment for me.

This incident caused me to seriously rethink my general approach. I realized that I had been trying to control and corral these mischievous kids but losing control of my own self in the process. A flustered person does not inspire much respect.

Over the next few weeks, my teaching style evolved to compensate for this. However, I didn’t consider how I had changed or what I had accomplished much until after I came back. The realization occurred to me as I was dispensing tips to a friend about how to deal with authority problems at her new job. I had actual, constructive advice (which I almost never do on any subject) gleaned from my trial-by-fire in Korealand.

Thus, I present the three most important maxims for exercising brutal authority:

1) Develop an impenetrable skin. People are going to say or do things that inevitable rankle you, but remaining calms is key. Learn to yell without yelling. If your emotions start to color your scoldings, this signals victory to most misbehaving children.

2) Lay down the lines. Two parts to this, you must make it clear what isn’t allowed and then convey with your body language and tone of voice when the rules are being violated. My default mode was friendly and joking, but I would quickly lose the jovial tone if some kid started acting out and adopt a very even and serious voice. From there, I would ratchet up the anger and noise until obeyed. However, because my rage wasn’t emotional, I could just as quickly switch back to being fun and kidding again.

3) Know when you’re beat. Some kids just don’t listen, so don’t waste your time with a situation you can’t handle. For me, this meant sending a kid down the hall to one of the Korean teachers who would ream them in their native tongue. Korean mothers can be quite scary, so threatening to inform their parents worked well also.

Things others have said